Do it your way.

Hot tires. Hot burgers. Hot meaningful artistic inspiration.

If I wanted to open this piece with a presumptuous cliché, I could say that Ian Worthington’s Bigtop Burger is the greatest adult animated series you’ve (maybe) never heard of. In the months and years leading up to its inception, Worthington (alias Worthikids) established his artistic oeuvre as a safe space for charming esoterica.

The earliest videos on the Worthikids channel tend to partake in no schedule, structure, or consistent theming beyond what Worthington himself finds particularly compelling. His current oldest upload is from a decade ago, reanimating a brief segment of The Eric Andre Show for just eighteen seconds. The dialogue for the clip is as follows:

HANNIBAL BURESS: So what are you gonna do, man?

ERIC ANDRE: … What?

BURESS: …In general.

ANDRE: I’m in a new band called Kuwait Grips.

BURESS: Can I get in the band?

ANDRE: Yeah!

BURESS: What do I do?

ANDRE: You play sleigh bells.

BURESS: Yeahhh!

ANDRE: Yeahhh…

BURESS: Sleigh bells…

ANDRE: Yeah, I’m… I’m on board for that.

As cartoon Eric Andre speaks the final line, gravity breaks down and he floats upward and away, along with the set pieces. Worthington’s version of the scene is significantly more dynamic, with fast cuts between the two and highly expressive caricatures. While I doubt he selected this particular clip for anything other than finding it funny, it ended up codifying some of the channel’s ethos: like the idea of playing sleigh bells in a band called Kuwait Grips, the vision works if you’re on board for it.

One of the cornerstones of supporting oneself off the craft of “content creation” is the often repressive force of distorting your creative ideas to fit prescriptive recipes for success. For example, I often feel pressured to streamline this very Substack into a more singular theme—because that’s what the experts say reels in subscribers, and therefore makes people look at your art, and could lead to some financial stability (which, lest we forget, is apparently the ultimate goal of art).

YouTube is certainly no different; you are far more likely to find successful creators with one dedicated purpose than ones who just make whatever they feel like. Worse yet, the already boxed-in output must then be rewritten and re-visualized to slot itself in alongside every other successful channel that is manicured to be-sure-to-like-and-subscribe formulaic perfection.

(Here’s another example: Worthington, who has proven quite successful in a decade of posting, has about 1.14 million subscribers at this moment. “Movie Recaps,” the first channel I found in searching YouTube for algorithm-optimized crap, began posting four years ago and exclusively inundates the site with AI-voiced summaries of popular films. It has 2.7 million subscribers.)

That decade-long backlog of animation on his channel is composed just about entirely of creations that Worthington simply wanted to make. This includes:

Animated re-imaginings of further clips from sources such as Eric Andre, Tim & Eric Awesome Show Great Job, and The Joy of Painting.

Multiple shorts paying homage to the Rankin-Bass 1970s stop motion style perfected by cartoonist Paul Coker Jr.

A short film entitled “CAPTAIN YAJIMA,” presented as a stop motion science fiction anime with entirely Japanese audio.

Full-length albums inspired by Shrek and SpongeBob Squarepants.

Two witches (named for Miram Margolyes and Joanna Lumley) debating the ethics of deceptive dating app practices.

There are no SEO-optimized titles. There are no clickbait thumbnails. Worthington does not play the YouTube game, and paradoxically, this is another key component of why he is successful. The skill he brings to the table as an artist joins the authenticity, presenting the viewer with a bespoke experience they cannot get anywhere else on YouTube—maybe even the entire internet. Not because of some magic formula, but simply because the vision is his and his alone.

One might be inclined to use marketing jargon to say he “zigs when others zag,” but I think the truth is that it’s simply the compelling nature of an undiluted, focused creative perspective. Worthington is not alone in this free-wheeling method (creators like Joel Haver and Jonni Peppers come to mind), but he’s certainly one of the big dogs.

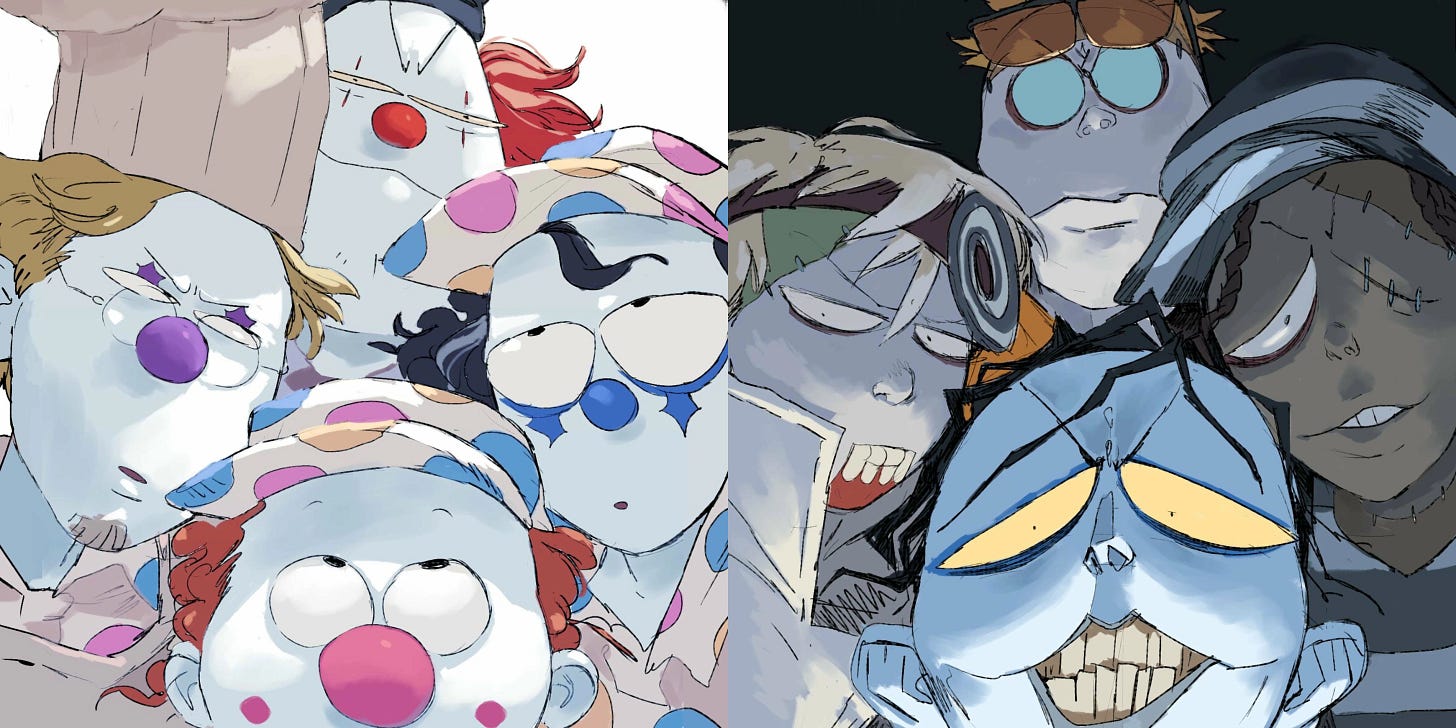

Bigtop Burger burst onto the Worthikids feed five years ago with STOVE, a two-point-five minute short where a gaggle of misfits in greasepaint hock burgers from a clown-themed truck. They are led by their boss, Steve, ostensibly a man with some decidedly otherworldly quirks. Each episode of the three-season series is just a couple minutes long. You could watch the official compilations of the first two seasons in roughly a half-hour.

Despite this paucity of runtime in a world where videos are stretched to fit in as many ads as possible, a complex story takes shape. After sufficient goofs and gags, the audience learns with time that Steve is a “real clown.” In the Bigtop Burger universe, this means that he is an alien from a distant planet of clown aliens whose world turns on the axis of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Cats.

(Though, on their planet, it was written eons ago by the species’ collective “forefather,” Clowndrew Lloyd Webber. Cats, the animal, do not exist there.)

During a ceremonial performance of the musical, Steve fumbled the role of Old Deuteronomy and was ostentatiously shot out of a giant cannon and banished down, down, down to the center of the Earth. This storyline, revealed visually in the season two finale, was baked into the theme song for season one (also written and performed by Worthington) from the very beginning.

Steve has a foil in Cesare, the undead Venetian owner of rival food truck Zomburger. His appearance, nomenclature, and supporting cast reference The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a classic silent horror film about a homicidal somnambulist. Cats and Caligari have a starring role in the narrative of Bigtop Burger seemingly just because Worthington is a fan. While Bigtop is viscerally unique, its uniqueness is carved from the influences that left large impacts on its creator. Like all art, it cannot exist without the traditions, creations, and ideas that paved a path towards its existence.

It feels ironic, though, that Bigtop Burger owes so much of its construction to Cats. Long before the disastrous 2019 film adaptation, the musical had been a bit of a redheaded stepchild in Webber’s resume. The show sold tickets upon tickets on Broadway for years. This was in part because its dance-focused, high-concept presentation made it easy to understand for New York City’s global tourists.

But that’s the thing. It was a dance-focused, high-concept presentation with a very thin plot based on a light poetry book, exclusively populated by adults in skin-tight costumes pretending to be felines.

While I prefer it to another wildly lucrative ALW creation, The Phantom of the Opera, I would estimate that this puts me in the minority. Cats has been maligned for many reasons: it’s too campy, there’s little story, it’s overly twee, the costumes are a shock to the system, there’s a weirdly erotic energy throughout, the gravitas is comical for a musical of its kind. And lest we forget, some people think it’s just kind of gay.

Most of these accusations could be reasonably lobbed at any Broadway or West End show, but I digress.

The point is that loving Cats is not always the most popular choice in the land, and its stock sank even lower with the release of that aforementioned film adaptation. Like The Eric Andre Show or Rankin-Bass cartoons, a cult following does not save it from being an acquired taste.

Worthington appreciates the Jellicle Ball without any care for naysayers, though. In September 2019—before the film crashed into theaters but after its marketing had already drawn considerable disdain—he created a brief homage on the Worthikids channel. In 27 seconds, he reanimated a brief segment of the trailer, where Jennifer Hudson’s Grizabella weakly sings “Memory” to the crooked moon.

Most of the video is treated with replete sincerity. There is little room for irony here, apart from some mildly silly expressions on Mr. Mistoffelees and Old Deuteronomy. The comments are full of wishes that the 2019 movie looked like the animation instead of itself. From the pen strokes and style, you can tell Worthington loves the musical everyone else is lambasting. And he doesn’t mind if everyone knows it.

After all, Cats is about looking past the surface and seeing the beauty in the people and things we turn away from.

Another key point still at which Worthington deviates from the current creative scene is in that he does not merely reference; he synthesizes his inspiration and uses it to create something entirely new and entirely his. In a pop culture landscape where so much of our entertainment and art is halfhearted gestures of “remember this,” Bigtop Burger is a creative being unto itself that is self-secure enough to wave to its ancestors without asking them to deliver quality and unique vision in its stead.

In short: rather than a bland Xerox, it is a well-reared child that learned independence as much as influence from its role models. As a result, baby Bigtop is its own person rather than a mirror of its predecessors.

In a now-deleted video, Worthington took five minutes to explain his affinity for the web series Ratboy Genius. Created by Ryan Dorin, Ratboy is the often uncanny animated chronicles of the titular rodent boy (seen above) and his vast cast of similarly unique-looking friends. The ensemble often speaks in computer-generated voices, singing songs composed by Dorin. In the mid-to-late 2010s, Ratboy became the center of much ironic fandom and internet memes. It’s so ugly! It’s so weird! How could anyone come up with this?

Underneath the strange trappings of Ratboy—or perhaps explicitly because of them—Dorin has led a unique and artistically effervescent life. He has a PhD in composition and had a small role as a 12-fingered pianist in the 1997 movie Gattaca. In the face of internet laughter, Dorin was undeterred and continued his passion projects without a modicum of slowing. He posts regularly to this day.

In the his tribute video, Worthington makes no bones about his appreciation for Ratboy Genius, declaring it to be borderline Oscar-worthy. He implores skeptical viewers to open their heart to the seemingly “cringe” creation.

“Just remember, Ryan Dorin makes this odd musical adventure regardless of naysayers who call it ‘cancerous’ or whatever,” he explains. “A lot of artists could learn a little from Ryan. Make your project your way, blemishes and all. Keep making it, even if it doesn’t quite have its audience yet. You might just make something special.”

You don’t have to take Worthington’s word for it. He walks the walk, and he’s found his audience. His animations have appeared on the famously eccentric adult swim programming block. Later Bigtop Burger episodes include voice talent from the likes of Alex Hirsch, creator of Gravity Falls. If you watch the enormous scroll of his Patreon patrons placed at the end of his videos, you might spy the name of Pendleton Ward, who created the generation-defining series Adventure Time.

This was not an overnight operation. As someone who’s been following his art for a long time, I recall making now almost decade-old posts where I grumble about how he deserved more attention. In the wake of Bigtop Burger’s finale, it seems that my wish finally came true.

But what makes it so Ian Worthington has over a million subscribers while Ryan Dorin has about 154,000? What is the special sauce that makes Bigtop Burger an internet phenomenon while other visionaries languish for years? It’s hard to say. Worthington is a skilled craftsman, but metrics do not inherently equal merit. If anything, his success as an earnest, out-of-the-box creator is a little miraculous in a landscape that doesn’t nurture rigid, algorithm-chasing garbage.

It is no doubt a profound challenge to consider doing it your way when our systems rarely seem to reward it. That profundity only grows tenfold when we remember that artists often succumb to these systems and algorithms for a justifiable reason: to keep themselves fed. But I think it’s imperative that we leave room to make at least some things our way. Even when it doesn’t bring in fat checks or sky-high view counts, it often has the power to nourish our spirits.