Eulogy for a Meathead

Among Rob Reiner's larger-than-life achievements, I remember Mike Stivic the most.

This post discusses sensitive subjects such as sexual violence, homophobia, homicide, hate crimes, and racism.

One of the most harrowing pieces of television I’ve ever seen is a sitcom two-parter. “Edith’s 50th Birthday,” from season 8 of the primetime comedy All in the Family, never stops being supremely difficult to watch. In the first part, we spend most of its endless, excruciating runtime watching endlessly sweet dingbat Edith Bunker nearly be raped in her own home by a stranger. The second part expands upon her resulting trauma, with a breathtaking performance by Jean Stapleton.

Most of the times that I watched it, though, All in the Family made me laugh. Not just chuckle or smile or halfheartedly exhale out my nose, actually ha-ha-ha laugh. Just a decade before sitcoms would regress back into a sanitized gift basket of wholesome family catchphrases, this show held an unflinching mirror up to the conversations happening in contemporary America. No subject was too taboo, too uncomfortable, or too raw. We all know this by now.

The Bunker Family—composed of Archie, Edith, daughter Gloria, and her husband Mike—explored every crevice of culture. Norman Lear’s little creation, borne from adapting a British sitcom, was a television dynasty. It led to the inception of The Jeffersons, Maude, Good Times, and piles of other programs indirectly or directly inspired by its candor. While memory of its massive artistic footprint has been eroded by time, its resonance remains, especially in a world where the culture war rules the day.

One of the countless other examples of its thematic bravery was embodied in the character Beverly LaSalle. Portrayed by Lori Shannon, Beverly was an unapologetic and larger-than-life drag queen who was a friend of the Bunkers, particularly Edith. Beverly was a recurring character, popping up in a few different storylines and hardly ever the butt of the joke. No, gay drag queen Beverly was openly loved and cheered for on this 1970s sitcom.

In her final appearance, Beverly is killed defending Mike from a mugging, which then escalates to a gay bashing. The cruelty of this hate crime shakes Edith’s pious Christian faith for the first time, prompting her to stop attending church—all right around the holidays. As Christmas dinner plays out and Edith’s low mood remains apparent, she exits and apologizes for “spoiling” things.

It is Mike, the atheist son-in-law played by Rob Reiner, who provides the comfort she needs to persevere.

MIKE: Ma… who are you mad at?

EDITH: I’m mad at God.

MIKE: Do you think God was responsible for what happened to Beverly?

EDITH: I don’t know! All I know is that Beverly was killed because of what he was. And we’re all supposed to be God’s children, it don’t make sense! I don’t understand nothin’ no more!

I must have watched this scene a dozen times in the days after I learned about Rob Reiner’s death. Its entire tone had been abruptly recharacterized, and it likely would be forever. When Mike slowly and quietly leaves the room at the end of the scene, leaving Edith to think things over, his once gentle exit now feels uniquely haunting.

While Mike’s comforting words—that maybe we’re not meant to understand everything, that what we need is people who try to be understanding at all—were pertinent, Edith’s lines stuck with me. Her tearful, uncomprehending frustration encapsulated how I’ve felt ever since the news broke and subsequently sunk into me like an anchor.

Reiner and his wife Michele had lived amazing lives, accomplishing incredible things that would stand the test of time, only to be snuffed out in an unthinkable act of violence. Just days before, we were celebrating Dick van Dyke, his father’s star performer, reaching a triple digit age in good health and happiness. Carl Reiner had died at 98 only a few years ago, after a peaceful evening watching television with Mel Brooks.

It doesn’t make sense. I don’t understand. But maybe I’m not supposed to.

After speaking to Mike, Edith returns to the dinner table. She steels herself and issues a holiday toast to the people she loves and how they hold her up, especially in such trying times. I suppose this is the way to go: leave the grisly details to the investigators and focus our discussions of the Reiners on love, art, and joy. And for me, Rob Reiner gave me the most joy when he was portraying Michael “Meathead” Stivic.

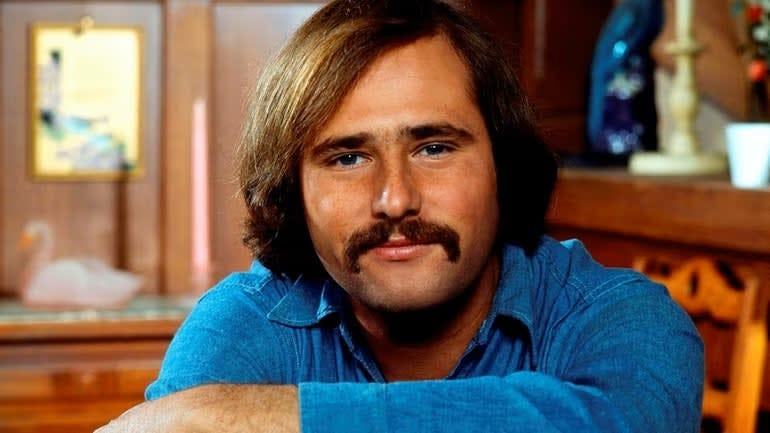

As a child, Mike reminded me so much of my father, who passed away almost exactly one year before Reiner. They had the same head of long brown hippie hair, the same mustache, the same academic tenacity, the same liberal views that caused them to lock horns with conservative relatives.

Part of the beauty of All in the Family and Mike’s character was that even he (whose views usually aligned more with the writers) was flawed, obnoxious, and often quite pigheaded. One of the show’s greatest strengths, in fact, was to gradually and naturally introduce the behaviors and psychology that led its characters down the ideological paths they walk once the show is underway.

In Edith’s case, we see her deep kindness and religious beliefs manifest in being unable to comprehend how someone could commit a hate crime. Over the course of many seasons, the audience gradually learns that Archie’s abrasive behavior and bigoted beliefs come from a number of places. These include his perennial fear of what he doesn’t understand, being unwilling to break the illusion that his abusive, violent father wasn’t harmful, and compartmentalizing trauma from serving in the Second World War. To him, Mike was the infamous “meathead,” because he was so foolish in his beliefs that he was “dead from the neck up.”

Mike acts as both his foil and an inverse mirror of his flaws and ideas. For all his bravado and righteous indignation, Mike can be wildly neurotic and insecure. He regularly spins out into hilarious bouts of anxious shouting when the pressure is on. When he yells in conversations with his wife, it is often less of a domineering power grab (that we expect in sitcom domestic disputes) and much more of an intensely nervous man not realizing his voice is way too big for the room. Reiner routinely delivers these lines with laugh-out-loud quality and razor-sharp timing.

Later on in the series, Edith gently tells Mike that part of the reason why Archie is so hard on him is because he represents all the things Archie never got to be. While Archie’s life reached its terminal level of quality early on, unable to attend school and shipped off to war, Mike has the privilege of learning, growing, and being open-minded enough to embrace change. In the same way that Archie fears what he doesn’t understand, he fears the way that Mike outpaces him in terms of lifestyle and intellect.

This is not to say that Mike is a Teflon genius.

Regarding that inverse mirror component, Mike is far from infallible in his ideology and how he expresses it. While he is vociferously against the bigotry that Archie espouses, his rhetoric and behavior represent more of the casual, well-intentioned bad habits that exist amongst liberals and even people further to the left than that.

One might liken it to the “white moderate” that Martin Luther King Junior references in his letter from a Birmingham jail; an individual who is superficially more enlightened than your bog standard racist, but can be even more harmful in the fight for liberation, particularly with regards to their hesitancy to criticize more ingrained institutional problems or even their own deep-seated biases. He comforts himself with not being a bigot, while neglecting the aspects of social justice that make him personally uncomfortable.

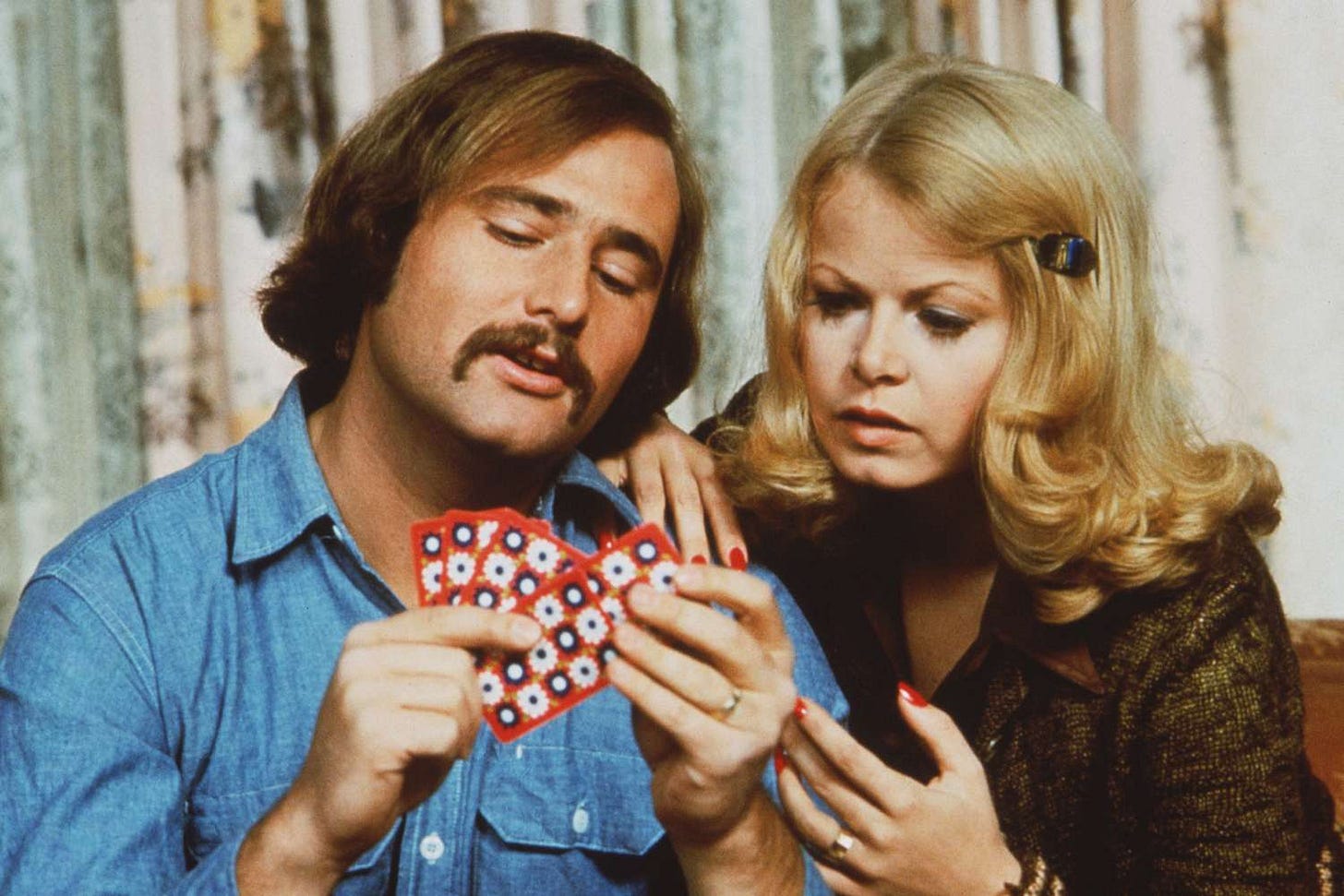

His wife Gloria regularly calls him out on moments where he expresses the kind of casual or even overt misogyny that might go overlooked by a man who identifies himself as a feminist ally. One particularly notable scene features Mike and Lionel Jefferson, the son of George and Weezy, playing a game in which they are meant to hash out personal feelings and communication styles.

While Mike is intensely combative about how he’s better than Archie because he is not a loud racist, Lionel points out that Mike engages in quite a bit of tokenizing. He frankly brings up how the vast majority of their conversations tend to revolve around hot button political issues relevant to the Black community, rather than just casual friendly conversation.

This episode, “The Games Bunkers Play,” dresses down Mike considerably in terms of his own flaws and foibles. But because All in the Family is a sitcom that deals in nuance and depth more than pithy catchphrases and adorable moments, this is not some fundamental destruction of his character. In fact, the little ego death that Mike experiences in this episode is meant to strengthen his character and give him more self-awareness.

With all these unique screenwriting challenges, Reiner rose to the occasion. He even wrote several of the show’s episodes. Mike was not created to be the endlessly adroit, educated liberal who would trounce Archie in games of wit. He was simply another kind of complex human, espousing the bad that can come with his belief system as much as the good.

Rob Reiner would go on to become far more famous for the award-winning, iconic films that would make up his oeuvre. As he has been mourned, his acting credits have mostly been relegated to a marginal footnote in his storied and rich career, deftly navigating different genres and setting the bar in many of them. Reiner portrayed characters in films and TV shows for years after All in the Family, including New Girl and The Wolf of Wall Street. Despite continued excellence in all of these, his work as a thespian remains something of a side street on the journey of his incredible career.

With all that said, his time on All the Family was critical to his burgeoning career in his early years and would be associated with him forever, even if it was almost exclusively among the older set. While he was alive, his tenure as Mike Stivic almost became a mean-spirited joke: whenever he would dole out some criticism of the Trump administration or someone in that orbit, conservatives on social media would denigrate his words by simply calling him a “meathead.” But to that end, his time as Mike is an inextricable piece of his career and artistic development. When he died, the nickname trended on Twitter.

For me, this is who Rob Reiner was. I’ve seen basically every episode of All in the Family many times over, some of them I would say in double-digit viewings. It never stops being funny and even salient to me, and Reiner’s portrayal of Mike is one of the key components of that. In the very same way that he would expertly move between war dramas, fantasy, thrillers, mockumentaries, and rom-coms, Reiner portrays Mike with both the laugh-out-loud comedy of an insecure academic and the heartfelt pathos of a loving son and husband.

The day that Reiner’s passing was announced, I queued up some episodes of All in the Family and just sat with the show I loved. As with the scene of Edith and Mike, I could tell even then that something about viewing it was changed forever. It was a heavy feeling.

It’s as if I’ve lost someone who, despite never knowing them at all, has been a part of my own family. Rob Reiner is a stranger to me. And yet still, I think that someone who makes you laugh and warms your heart for decades can be a sort of friend, even if it’s through a screen, on film transported from the past. So among all the tributes issued to the timeless director of world-changing films, I will pay homage to the Meathead who made me laugh. Again and again and again.